Matchbox Brothers (2013-16)

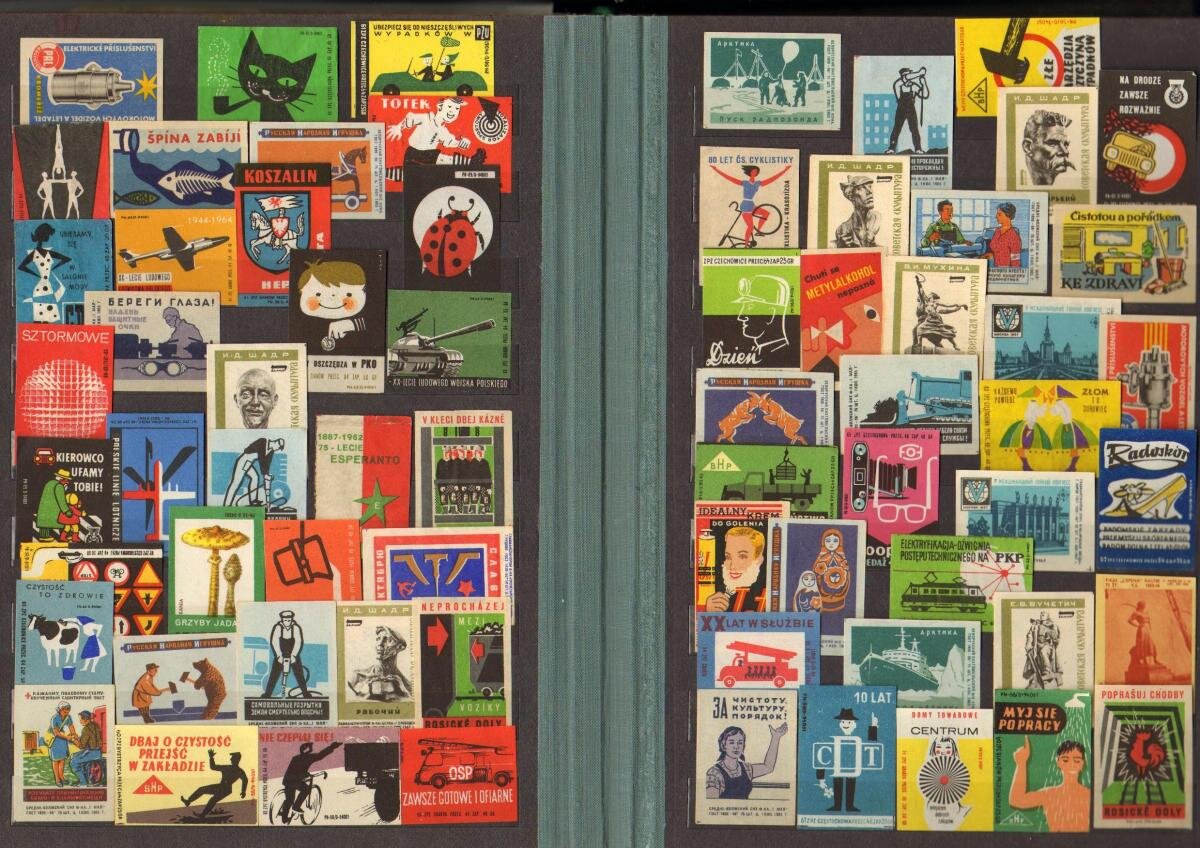

A few years back I inherited a matchbox cover album from my Polish grandfather, used as inspiration for a series of drawings, first shown at the Polish Social and Cultural Association in London, 2013. In 2014 these were combined with a fictional text I wrote and presented over a one week show at the Hundred Years Gallery, a dynamic art space in Hoxton. In 2016 the drawings and text were made into a self-published book entitled Matchbox Brothers launched at The Exchange, an artist-led project in Brunswick East.

To purchase a copy of the book please get in touch.

Fictional Text – Matchbox Brothers

Matuesz escaped the war when he fled to London, leaving his brother Jarosław in Poland. He married a woman called Ewa and settled down with a family and a career. On a day to day basis he was a strict and upstanding citizen. However he suffered from a weakness of character which made him more susceptible to the grasp of an oppressive regime.

He was a regular at the Polish Club, where he had several good friends. Sometimes in the evening he would invite them all back to his home for lively vodka dinners. They would play Loterika and smoke to high heaven. The light switches in his room, cheap plastic were tarnished a yellowing ivory. Red baize pin boards went all around the dining room and were used for mounting his coin collections on. Magnifying glasses laid here and there. A bureau in the corner was stuffed with gummed stamp hinges, envelopes and old letters from home.

He began compiling an album of Polish matchbox covers. Collecting state regulated images in a ‘free’ society, he was partly under the spell of communism still. At leisure on an evening once home from work, and freed of his parental duties, he would sit in his back room and construct his collections as some microcosm of utopia. Colourful images of a bygone time would sail past his eyes triggering fond memories…

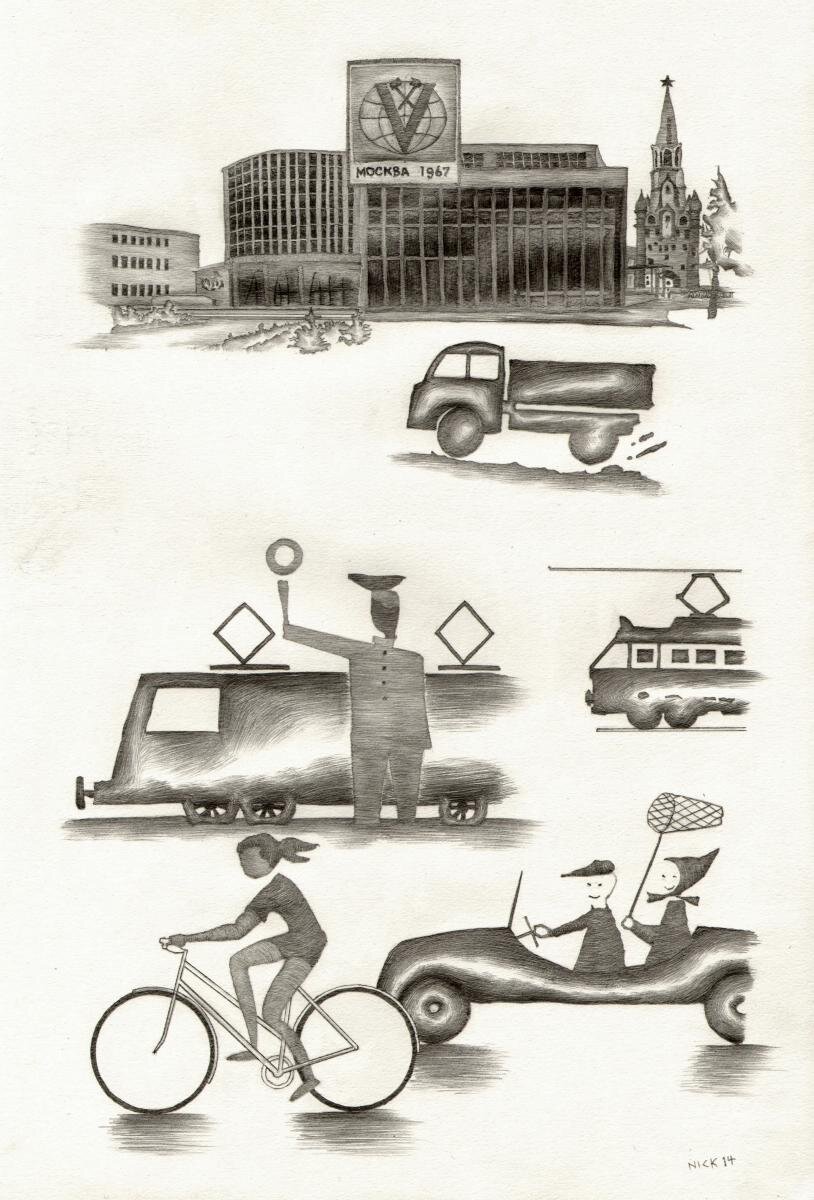

…Coal wagons rattling through Upper Silesia, fuel for spick and span factory towns in the south. Head to Warsaw for the latest fashion, a polka dot dress to stand out from the crowd in, clean cut suit, tie and trilby. Icebreakers and cruisers, sailing yachts and crafts, boats to be seen on the Baltic!

Then his wife would call from the front room, the kids were demanding attention and needed tucking into bed. He would dangle small pieces of kabanos from the larder shelf and make them leap about until they had not an ounce of energy.

The next day he hopped on his bicycle, he had to be at the offices of the town council for nine. This new job working as an architect for Tower Hamlets certainly kept him busy. A project was about to start this morning and Matuesz had been assigned to it. He was briefed by his manager and learnt it was only a stone’s throw away. I’ll pass by on the way home and have a look, he thought. It was a balmy summers evening when he left, already late, but guaranteed to be sunny for a few more hours yet. Fifteen minutes and he was there. Torn posters advertising a dancehall event in Bethnal Green flapped from a hoarding. Through a broken fence panel he was afforded a view of the site. The remains of a bomb struck terrace stood starkly against the neat row of Victorian townhouses behind. He shuddered perceptibly and grimaced at the thought of what this place represented. Not for much longer though.

The visit left a bitter taste in his mouth, and to try and expunge it he called by at Marek’s.

“Will you be taking a delivery this week?” asked Marek.

“Yes, my wife wants some cabbage and ingredients for making soup.” replied Matuesz. “What day will you be passing my house?”

“Probably Monday evening.”

“That should be fine, my wife will be in.” Then he bought as an afterthought a bag of Kruwki, and lined his pockets with them for when he got home.

Several weeks later the project was well underway. At the end of another busy week Matuesz was just on his way home after finishing late that day. He had been on a site inspection to see how building work was taking shape. Everything looked fine, the foundations had been laid and the first and second levels finished. The lift shaft was almost complete. The skeleton of the building was empty, the places where the rooms would rest darkened cavities. As he recalled its last impression on him he was assailed by a sinking feeling. There was no logical explanation for this, just recollections of a dark angular nature. Communist construction and its connotations clouded his thoughts, filling them with gloom. Gazing about the landscape in the East End it differed little, he hailed a bus and boarded quickly, glancing back over his shoulder as if expecting a blitz.

He sat on the top deck at the front, knowing the panoramic view would cheer his spirits. As they inched towards the city imposing buildings cloaked in grey stone rose significantly into sight. The breadth and wealth of history humbled him by its scale and grandeur. The dome of St Paul’s, like a pristine white sphere, surged free from the black stench. Ribbons of grey smog clung to its circumference, like a maypole in murky march. Even on a day with leaden shadows that plumbed the deepest depths of an alcove, the architectural wonders of the city would always set his pulse racing.

Eventually the bus neared the end of its route, and instead of alighting he restamped his ticket and stayed for the return journey. A couple of stops before, unable to face the prospect of another walk through those ill-fated streets he got off. He turned down an alley, not stopping to admire the dereliction of a Victorian slum over the fence. Once back on the main road his house at the junction of two roads was visible.

His eldest son greeted him as he entered. “Where have you been father?”

His explanations were hardly over when a tumbling came from the direction of the stairs. Tousled and tangled in a heap they appeared, his two troublesome daughters. Never out of one another’s way, they called in unison “Tatusz, Tatusz, have you been to Mareks?”

“I have a white rabbit” he said, and tugged at a pair of invisible ears in his pocket. Wondrous expressions turned to dismay and plain hard done by.

“Matuesz, don’t tease them”, his wife scolded. He eased two treats from his pocket and won admiration back from his girls. “Now come into the study and have some supper.” A bowl of steaming bigos and bread lay on the table. He attacked it with the appetite of a hungry wolf, she sipping lemon tea from a glass, daintily. After eating he moved to the couch and gazed into the middle distance. Turning over events in his mind his thoughts were relived.

“Ewa, my training at the architecture school does not go amiss. This latest project I have been assigned to at work makes full use of my knowledge and is rewarding. But why, each time that I visit the place, does it send a shiver up my spine, makes me feel as if I am barely out of the grasp of those communists? Dark, drab, buildings that they want to throw up in every corner of the U.K. It will be an ugly kingdom of post war tower blocks and corrugated concrete garages as far as the eye can see.”

His eyes slipped to the walls around him and sought solace in the collections of coins and cards contained there. He glanced down into his bureau and the album of matchbox covers lay open at a page of suspiciously clean and underpopulated communities, a school, offices and a town among them. He thought of his brother Jarosław, an artist. He lives happily in the system, conforms and slavishly churns out images for the cause. I could learn a lot from him!? Seizing a pen and paper, he scribbled a hasty note to his brother. It elucidated his worst fears and described the guilt that he felt whilst carrying out his work every day.

Dear Jarosław,

I am becoming a prisoner in my own home. I can hardly walk down the street without being oppressed by the buildings I see. I am becoming the jailer too now by participating in the design of government social housing experiments. Supposed solutions for those who don’t have to suffer them.

When I delve into my matchbox covers album at the end of a day it is like a comforting balm. The images take me back to an age of innocence in my childhood. They portray stability in a world that has brought too many disappointments. Once upon a time they were at every corner, but now I see them only as unattainable idylls. The reality of time has shown them to be flawed.

You must send me another batch of the matchbox labels. I know it is a precarious operation to obtain them and carries with it many risks but…. Please! It is the only time of the day when I have five minutes for myself that I can truly unwind. When I look at the labels, a great calm comes across me dispelling all anxieties. I forget all the injustices, and only feel the good of my place in society.

Yours, Matuesz

Jarosław is a freedom fighter. He conceals messages in his artwork that are designed to undermine communist authority. He feels that art should be used to make people see the reality of their predicament. He is a believer that art should always be used to portray the truth. Through his work, and in spite of the difficulties involved with working under the regime, he endeavours to enlighten society in his own way. Though this often meant working in a covert manner.

After he had graduated from the fine art school in Warsaw he made the acquaintance of an official, and gained himself a post as a graphic designer working for the state. Through hard work and loyalty he eventually gained the position from which he could make his voice heard, that of matchbox designer. The party line was that all images produced and printed must be designed to lull you into a false sense of security. The bright colours and positive attitude, the belief in one’s country and its accomplishments.

When Jarosław received the letter from Matuesz he was fraught with anxiety. He thought long and hard about his request to bring more matchbox labels. He felt that it would be good for his brother’s peace of mind, but equally was worried that they might just be spreading a fear that by the tone of his letter was already haunting him. The labels were simply another form of propaganda which his brother was always more susceptible to anyway.

Back in Poland the communist way of life had come naturally to him, and he never ventured to question anything. The reassurance of equal standing and each man doing his bit for society captured his imagination. He even tried to embody its ideals in his architectural practise, and would submit specially made plans to the board where he worked. In the placing of struts and supports, he would always make sure that the whole framework of the building functioned by supporting itself. Even if one piece was missing the whole structure would risk collapse.

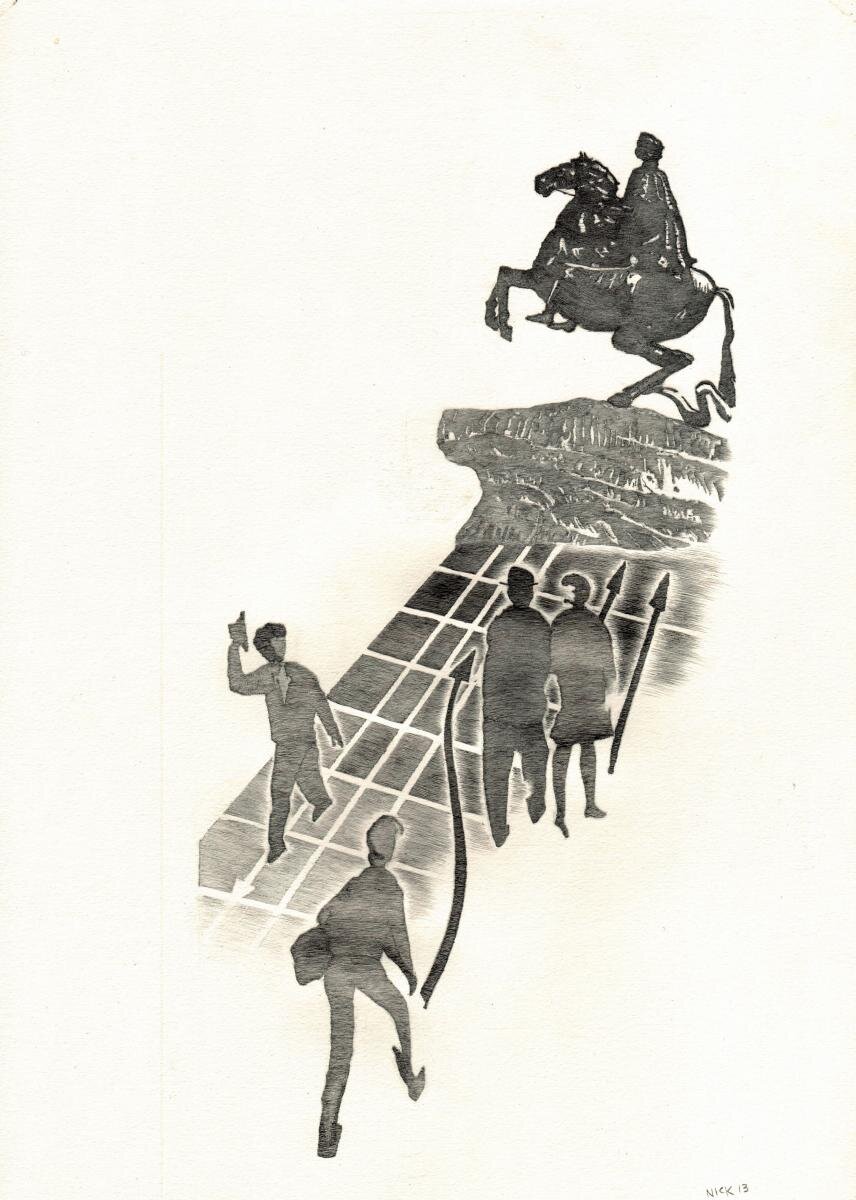

Jarosław decided to pay Matuesz a visit, and to take with him another batch of the cards. Two days before leaving he stole out of his studio apartment in Ulica Marszalowska. He crept stealthily past darkened doorways and through dimly lit squares. Rows of bomb scarred houses towered above him from all sides. Balconies with wrought iron fretwork rusting away looked down on him. From one a canary singing a mournful tune swung. It was watched over by a solitary figure who occasionally averted his view downwards. Jarosław caught his eye, and a meaningful look was exchanged. Then his watcher melted into the background as if behind a closing curtain. He reappeared downstairs, opened the latch and beckoned him to come in. The moment he entered the flash of a shabby jacket caught his eye. Matchbox labels in a plethora of colours hung like bunting from its interior. His breath was taken for a moment before he regained his composure.

“Wojtek, I have not been to see you for such a long time. Do you have anything new to show me?”

Wojtek reached into his satchel and recovered a small plastic wallet. It contained three recently removed matchbox labels stiff with steam like starch still. “These are from my personal collection” he answered. I have recently acquired them from a small individually owned press, a limited edition print. The run was only one thousand copies and I have obtained ten. The condition is impeccable and features a series of images that illustrate the soviet space race.” Jarosław, knowing his brothers fascination with all things soviet and domineering in spirit, couldn’t resist the opportunity. The trade was made, and each went in his separate direction.

It was twilight now, the hour when the fizzing sodium lamps spat into life, giving out a glow which fused with the setting sun. He made it back just in time to pack his bags securing the labels safely within. The journey to the U.K was a nerve-racking one. Three officials had barked questions at him continuously for three hours: “Where did he purchase the labels? Whom from? Why? For what reason was he visiting the country?” He answered that he was an artist working for the Polish government, and showed them his papers. “The labels are proofs bound for the printing press of a famous Match producer in the U.K. They bought the rights as part of an advertising campaign.”

The next morning Jarosław arrived at a busy interchange in London. It was his first trip to the capital. He stood outside as an indistinguishable blur of taxis, cars, buses, people and bikes thundered past. He made straight for an art gallery a friend had told him of, it was the only thing he could possibly conjecture after such a stressful trip. An exhibition dedicated to the work of English neo primitivism was being held, and Stanley Spencer was a painter whom he really admired. Quaint rural scenes of rustic village pleasure, cricketers in their whites bowling lethargically on a Sunday afternoon. You always had that sense that time had stopped, that the ducks waiting two by two at the zebra crossing had purpose in their arched beaks and bills. How peaceful things were in this green and pleasant land, he thought. How different from back home, but how artists use the same techniques. His use of subtlety to conceal a message. But this is what I am doing myself! In a moment of artistic revelation he rushed out of the gallery.

He remembered a small place his brother had told him about around the corner from the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington. It was a place of no extraordinary consequence, just a humble wooden brown frontage with the name Dakis above the door. The waiter spoke to him in Polish as he entered, asking him a reel of questions. Once again he felt himself to be under the interrogators spotlight. He replied “My friend, what is the meaning of this? I have literally just got off the boat from Poland, and have had a long trip. Where is the warmth I was led to expect!?”

The waiter apologized and the ensuing conversation eradicated all distrust. The cold look melting from his face when he recalled one of his favourite customers. “Matuesz, of course, I know him well, he used to have lodgings very close to this place. We used to see a lot of him. But now I heard he has moved east, a new job and a new family to house taking him there.”

“Yes, I believe he resides in Forest Gate, I have his address here, and I will pay him a visit after work” replied Jarosław. He requested a few places of general interest to Poles: where he could find the ballet, where he could find a shop, the embassy, the Polish and RAF clubs. Leaving the cafe he casually sauntered down the street flipping a matchbox from his pocket and sparking up a cigarette. A black cat sucking on a pipe with a Cheshire cats grin beamed back up at him from the matchbox cover. It highlighted his mood, and how the friendly disposition of the cafe staff had dissipated all thoughts of their immediate hostility. Maybe that’s just how they are with strangers, he concluded benevolently. A distant chime alerted him to the fact that the working day was drawing to a close. He thought about his brother, that he must be saddling up to go home by now, attaching the technical tools of his trade to his bicycle. A dark cloud was pushing across the horizon foreboding rain, and dampness hung in the air.

He arrived at a leafy suburban street lined with terraced houses. Gigantic structures of London Planes rose up above him on either side with their gnarled and twisted torsos. A meshwork of branches overhead, obscuring all sky from view. Fragments of light breaking through, piercing the dark underbelly of the leaves and limbs below. He disappeared into the undergrowth of a front garden. Arriving at the top of the path, he timidly knocked on the door, unsure as to whether it was the dwelling he searched for. Three eager faces peered through the hexagonal plates of glass. “Uncle, Uncle!” they shouted as their mother opened the door. Entering with powerful strides he took the children with him, one left hanging from each leg. He embraced his brother heartily and gave his wife three pecks on the cheek. To the eldest son a solemn handshake was the required form of greeting. Matuesz seeing this, made light of the situation by saying “he must have been knee high to a grasshopper last time he saw you.”

Embarrassed his son slunk into a corner muttering “he likes practising silly English phrases like that, you must excuse him”.

“When was the last time you saw the girls Jarosław?” his wife said.

“It wasn’t long ago, I remember our sister brought them to pay me a visit at the studio. The place was a hive of frenzied activity, I was working on some designs that would be displayed from prominent billboards in the city.”

His brother smoothed out his prematurely white thinning hair, pushing the thick set black glasses back onto the bridge of his nose. He gave a decisive snort, and looked wearily to the floor. “Ewa, it is way past the children’s bedtime, and bring some vodka glasses on the way back with you.” Half an hour later a chinking sound indicated welcoming toasts were impending. Matuesz withdrew from his bureau a bottle of the finest Wyborova, “Na zdrowie” echoed through the house, and good health was drank to one and all. Jarosław started to relate his tale of a traumatic trip, how all had been saved when he met some mutual acquaintances, who put the faith of god back into meeting strangers abroad. Ewa retired giggling uncontrollably, citing somebody would have to get up in the morning to bathe and breakfast the children.

Matuesz waved her out of the door, and now he was in his element. The inhibited effect of soberness lifted, he propounded his views on every subject. “Restrictions of movement, curfews, corruption and bribes”. Jarosław cringed at the perceptiveness of his brothers observations.

“Things have only got worse.” he replied. “Now people are snatched from the street and not even family and friends will talk about it for fear of reprisals. Deserting Poland was an arduous enough experience. Having to flee with terror to save your skin and leaving loved ones behind. Thousands of miles of enduring great hardships, and always at the risk of being exposed. Never being able to let your guard down for a minute. When you finally arrive you throw yourself into the arms of the allies, but you are a stranger in a strange land. A foreigner on friendly soil hopefully, where all you can do is strive for a better existence.”

“I’ve tried to do my best” mumbled Matuesz. He shook his head as if to clear a blind spot from his vision. Coming back with greater clarity. “Let’s drink to the future of Poland.” And he charged their glasses.

“Here’s to Poland, and its people” chimed in his brother. They both drank and sank further back into the red settee. Jarosław offered a cigarette to Matuesz which he watched curl up and about his moustache before breaking the silence. “Tell me about the letter. I could sense some unrest, paranoia even, maybe.”

“Everybody has their demons, and mine have been in hot pursuit since I left Poland. Now they haunt me like spectres, relentless in their will. It’s like having a searchlight trained on my every movement that swoops to and fro and leaves no stone in my life unturned. They blame it on the war, and try to tell you that people want quick construction and standardized measurements. But the reality is I am the one who is ultimately responsible for the spreading of this disease. The greatest irony of it all is that I managed to escape building these ‘prison cells’ once. Only to find myself in another country inflicting exactly the same fate on millions more unfortunate others now. The only thing that makes me feel better is when I come home and submerge myself in the labels. Then a great sense of relief comes flooding over me and I just feel that I am acting out of duty. Once more a useful cog in the works of the town councils machinery.” There was a cry from his wife, and Matuesz went bustling upstairs to check on the children.

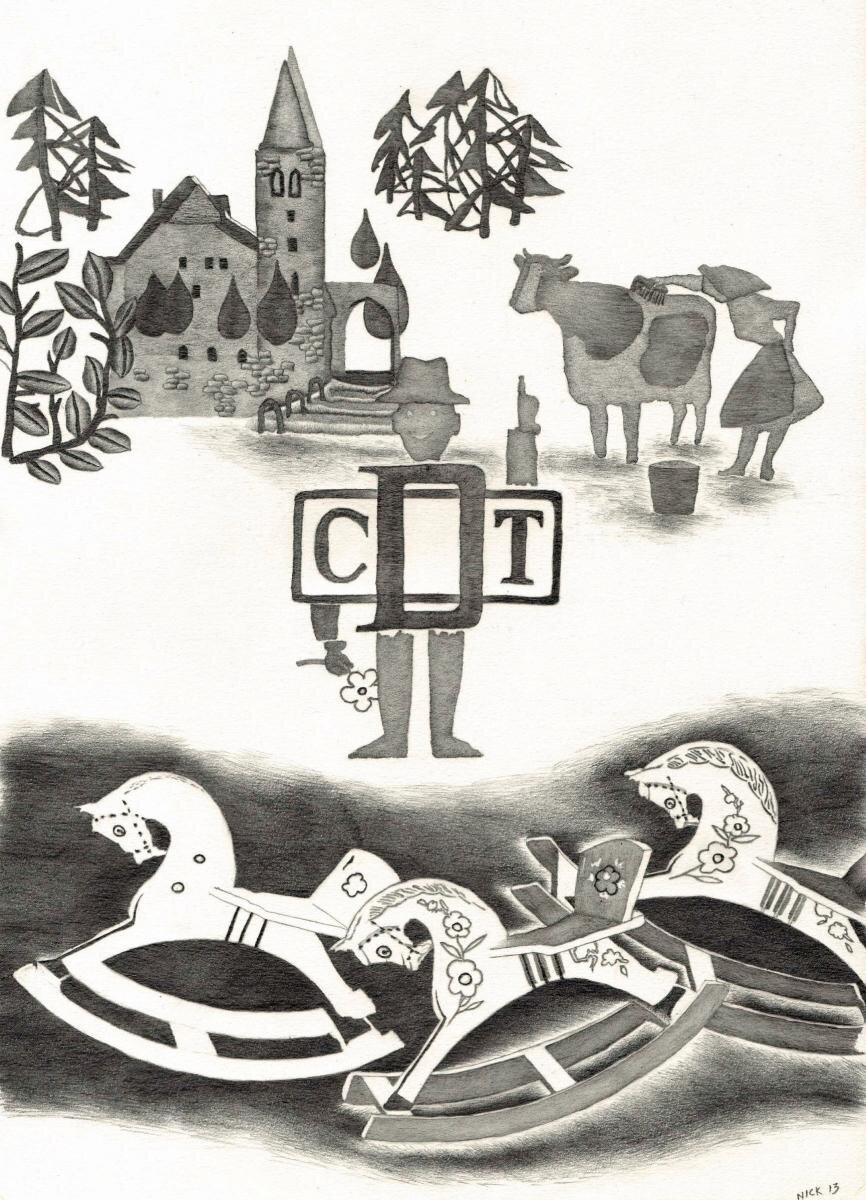

Meanwhile Jarosław was left to his own devices in the study. He rifled through some albums on the bookshelf and pulled out a couple at random. One on rare stamps and another with no obvious subject, just a plastic cover to protect it from the dust. This one he turned delicately, and with a real curiosity as to what was contained within. He opened it and allowed its musty aroma to envelope him at each turn of the page. Rows and rows of yellowing matchbox labels contained behind clear plastic. Grouped in series, colour coded, in orderly patterns, but the more and more that he looked at them all he could see was signs of danger. Lurid reds stamped with bright white Cyrillic’s! Seats of power, conference centres, palaces to new learning, ministries to entertainment and education. Buildings that paid tribute to the strength and breadth of soviet culture as far as the eye could see. Even as an architect surely Matuesz was not only collecting these out of admiration for their formal properties. He felt like spluttering, more heroes of the revolution, and more sickening images of forced cooperation. Nurses patching up soldiers on their rounds, comrades falling in love on the factory floor.

The darkness of his vision was broken by Matuesz entering. “I see you found the album, that’s the one I spoke about in the letter. It really does the trick of levelling me when I’ve had a tough day at the office.”

“The imagery is very powerful.” Jarosław commented. “State prescriptive drugs for the masses” he muttered. “Though I’m sure this is not the best way to combat your problems. Matuesz, you have asked me to bring more labels, and I have brought them with me. But I am reluctant to give them to you now when I see how dependant you have become on their calming influence. It is understandable that a massive change has taken place in your life. Socially and politically you inhabit an entirely different realm. It is easy to see how you use the labels as a force to temper the difference between these opposites. Transition is a difficult thing to cope with. You obviously find it easier to get on in the new world, if you take along a little of your old one too.” Convincing himself, he reached into his suitcase, and pulled out a plastic wallet. Matuesz’s eyes lit up. “I purchased these from a dealer ‘friend’ in Warsaw before I left”, and he handed over the labels he had brought.

Matuesz received them gratefully. Went to his desk, broke open the seal and tapped them gently into his hand. He examined them minutely for peculiarities, then, finding none, was lost in the image. Misty eyed he reached for his matchbox label identifier a few moments later, before proceeding to enter them all onto a page that documented soviet feats of exploration. Jarosław was shocked by his brother’s submissive streak. His strength of character had evaporated on the spot. How easily he had succumbed to the faintest hope made possible by the offer of the labels. For the price of respite from his daily feelings of guilt, he would be happy to trade in his will. The legacy of the communists runs deep, he thought. Even if it’s not in your actions and your words, can be in your mannerisms and your ideas. Matuesz is not a leader, but as part of the system of the town councils housing programme he considers himself to be a contributory factor. “Matuesz”, he reached out with sympathy in his voice, “I wish that there was a better way for you to harbour this terror in your soul. For it is a presence that is ingrained in you and as such ad infinitum.”

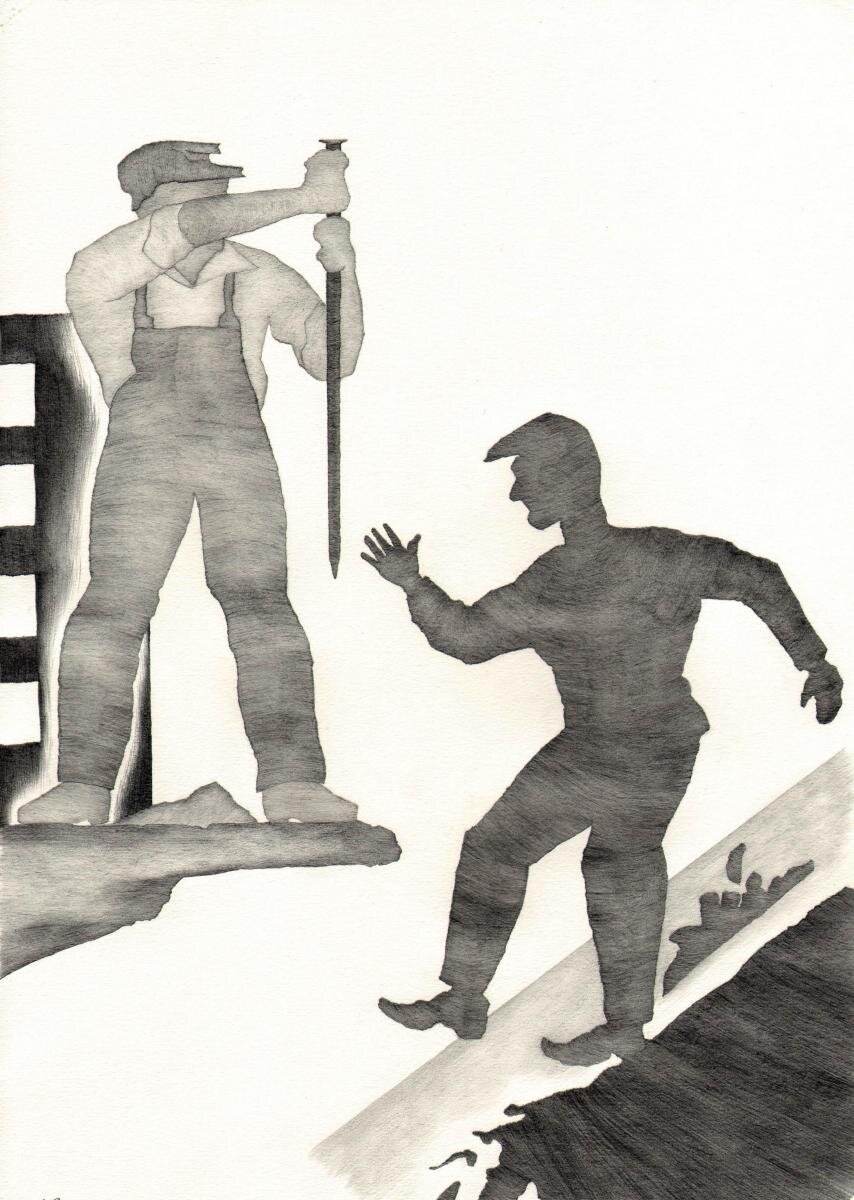

“Since I have arrived something has been on my mind that I could not tell you. The precarious balance you have struck up with life not needing any upsetting. It has been a great difficulty keeping it a secret, but now the time has come when I know I must speak. The billboard project that I have been busy with of late. It came into being through a series of meetings that happened between myself and Monika. She is a notorious figure on the Warsaw underground art scene. She came to my studio one evening where I showed her the proofs for the matchbox labels I had finished. She said to me, “Jarosław, I find your drawings really interesting. They strike a fine balance between what is risqué and what is considered orthodox. They will appeal to people’s sense of judgement. Making them question whether the citizen is falling accidentally down the hole, or if he is falling down a hole dug by a government operative. Their poster-like qualities of simplicity and boldness make them ideal for a project I have in mind. I picture them visible by thousands, several storeys up, high above the chimney of the old iron ore smelting foundry. Towering over the landscape, they will flare like an oil rigs flame, then be gone leaving a trail like the trace of a sparkler, just a message suspended in the air.”

As she elaborated on her vision I was in raptures. Then as she paused for breath I dared to break her dynamic flow “Monika, I am flattered that you have such grand schemes in your mind. This idea of a temporary existence is sheer brilliance, and will leave us highly untraceable by the authorities.

“In all that I do I excel in the art of the elusive” she replied. “The raw materials for the installation of the temporary artwork shall come from a factory that I know in Czestochowa” she said. “They produce matchsticks and have machinery large enough to make them one metre high. An order of two hundred should suffice for our needs. Though before we make an order I think we need to sound the place out by paying them a little visit.”

“And we have the perfect cover” I said. “As a designer of the matchbox labels I am probably the least likely person they would expect any underhand or dubious goings on to be happening with. I would be perfectly within my rights to go. You could accompany me perhaps too if you wish, as designers assistant.” Monika nodded assent. “I would make a pretence that I am there on quality control purposes. Checking that proofs that have come down have been successfully transferred onto the matchboxes, that the colour and dimensions are correct.” Monika promised to do her best to organize the trip for the end of the month.”

Matuesz, who up until this point had been listening intently, now displayed an expression of shock and disbelief. As this new information sunk in, the full meaning of its words hit home. “You mean to say, that your collusion with this woman signifies involvement with a hostile party. Making you are a collaborator!? To think you had this wayward streak, when I had always believed you to be a conformer. All those years of looking up at you. Trying to follow in your footsteps, by setting a good example through my work. I thought I would learn from you, and then it turns out you abuse the power the government entrusts in you. I am beyond disappointment. Notwithstanding that you attempt to conspire against the citizens of Warsaw. Do you realize how serious a crime that is, and what punishment it carries?”

Jarosław hung his head. His brother’s tirade continued. “Every day that I spend in this country I go through a constant battle, and am torn in two. The guilt that I feel through the factor I play in the fate of these hospitable people. When all they give me back in return is a career, a roof over my head and a place to settle and be free of the horrors still haunting those at home. And I live on in the apathy of a country so far removed from the political turmoil of my own land. Whilst my countrymen seal their lips for fear of reprimand, I am free to say what I feel. And the hallucinations that I suffer, and which bring forth unpleasant feelings. I try to cope by telling myself that I have a valid role in English society and that with time they will subside. That the more right I do by the people that I house, they will become less intense, and tell less on my conscience.”

Jarosław, feeling pity for his brother. “Matuesz, for the sake of a quiet life, I can see that all you wish for is to keep a low profile. To become a fully functioning component of this new society with as little fuss as possible. But this is also your opportunity to break the mould. So that one day maybe you will be recognized as other than just that architect of solitary cells. But it seems that even here, those demons are inescapable. That the onslaught of communism has already taken its toll in the housing sector.” He picked up the album from the table with intent. Turned through several pages, then deliberating slowly chose one to speak about. “What do you see when you look at this label?”

“Why, only the glory! Roaring steam engines rushing through the Polish countryside, hyper efficient, transporting food, produce, goods and people between towns and cities at breakneck speed.”

Jarosław sighed dejectedly he’s a goner, lost to the system, hook, line and sinker. He drew in a breath and elevated his position. Perhaps in the vane hope that the extra height would make him seem more authoritative. “Matuesz, look more closely. Don’t you see this speaks volumes about the injustice which lies at the heart of our government? The mercilessness of the non-stop express service over the smaller locomotive which chugs along and must give way.”

Matuesz retrieved his magnifying glass and hovered it a few inches over the label. Still nothing registered. He screwed up his eyes but nothing showed on his countenance save devotion. “Matuesz, you must realize that I am the designer behind these cards. Back in Warsaw I hold lectures in draughty warehouses and underground resistance libraries to explain their significance. I see the moment of clarity on many a young face. How it lights up like a beacon at the assimilation of such data. Then I come here to see my own flesh and blood with a mind like mush. Hooked and dependent and it breaks my heart.” He glanced to Matuesz who gave him a glassy eyed look. “How about this next image?”

Matuesz replied “It is part of a series on edible woodland mushrooms.”

“Yes, but look more closely and you will notice that the brown and red speckling on the gills gives them away as in fact poisonous. It is known to cause mass paranoia, a feeling that is not uncommon in today’s society.”

Again nothing registered. Leafing to another page he came to rest on the face of a man sat cowering at the steering wheel of his car. His brow was furrowed and he was anxious looking. Outside it was oppressively dark and branches clasped terrifyingly over his head. “What is your interpretation of this?”

Matuesz replied that he was probably driving home after a hard day at work. His long face made worse by the violent wrenching of the trees overhead.

“Can you not see how lonely he is, and frightened to his wits end by the world about him!?” He cast a look of exasperation in his direction, not one iota of comprehension showed on Matuesz’s face. “What do you think when you see this woman spinning her parasol in this frenzy of consumer activity?”

“Customers flocking to the shops” replied Matuesz innocently. “They have money to spend and when they see an advertisement they are lured by the thought of a good bargain too.”

“The reality is that the people are hypnotized, they walk in a daze through shopping precincts. A friend tells them about a chic Parisian jacket, but for all they search high and low they cannot find anything that even barely resembles it. The only things on display in the windows are of drab grey cotton.”

In a moment of blinding clarity Matuesz struck his head. “The people are being deceived!” he exclaimed. “The way that you have drawn the parasol amidst a fog that clouds the senses of the consumers, it makes them powerless to resist. “Jarosław, you have made me realize the error in my observations on this Poland I have left behind.” His brother breathed a sigh of relief.

“From today I will not be closely tailed by the spectres that used to haunt me daily anymore. I am a free man. I have been enlightened and for that I am grateful to you. My need for the album is quenched, I desire no more to have it close by. I do not need it to remind me of the regime back at home, or that I might need to bring elements of it here with me. I do not need it so that I have something to give me faith through the dark days, when the presence of the communist structure is ominous. I will look to the future with renewed optimism, and put out my feelers in a different direction. I will confront my past without fear”. He looked to Jarosław who returned an assuring gaze.

“My work at the town council shall suffer no more from the legacy of this dark history. I shall be able to work, design, think and posit ideas about future developments with a clear mind and conscience. The day to day pragmatics of the situation will never change, the allotted space given to a unit within an inner city built up area won’t differ. I will still be responsible for housing countless families in matchbox cities miles high. And that’s one communist trait that will never be expunged from my system. And if I ever lose my way I will refer to your world of concealed messages and take strength in their wise words, happy that they bring me into closer contact with you.”

Jarosław returned to Poland in a melancholic mood. Pensively he pondered upon the ill fortune that his brother had endured. To escape from being a prisoner of war, only to be confined once again in his new home as a prisoner of the state. As he sat on the tram to his studio next morning he vowed under his breath never to give up the fight against communism. That his messages should come through loud and clear like foghorns in a bleary, dreary Baltic.

The good thing is Matuesz is now feeling more at ease with his situation, he thought. Though he has escaped, that system was still in need of his services. They probably replaced him as if he were no more valuable than a nut or a bolt, but the important thing is he did evade capture. They will pursue him relentlessly, though only in his imagination where that sense of paranoia will make it feel tenfold. The darkened clouds he raves on about, that collect in the corners of buildings altering their shape so he sees cavities where he should see potential for future accommodation won’t dissipate. Row after row of empty eyeball sockets, vigilant but vacant. Now he finds his place in a new society. He is filling his old shoes. His function to house tenants in an economical but humane way is the same. The immediate governing systems are different but something survives of that old communist ideology, something that was deeply rooted in Matuesz’s character anyway.

The next morning, he telephoned Monika. After a while she answered and they spoke in friendly terms about his trip, her enquiring about his family. He didn’t tell her a word of what he had told his brother, not to mention the fact that he had revealed his true political identity. It was a detail that could only lead to complications in the future. “What have you arranged with regards to visiting the Matchstick factory?”

“I have been in communication with them” she said. “Once they heard we were of an artistic ilk they promptly came back with an offer that was too good to be true. As part of annual celebrations of the leader’s ascent into power a bust is to be unveiled. The business of the factory being matchmaking they have decided to put their resources to good use. They have heard of an artist that produces larger than life size portraits made from matchsticks. The opportunity afforded to them by your coincidental trip to check on proofs was just too good to be true. They would like to arrange for us to go down a day early in order to have time to complete this monumental match building task”.

Jarosław hung up, his mind was in a whirl, thoughts of his brother mingled with more immediate concerns about preparation he would have to do in advance of executing this commission. The next day after checking with Monika exact times and dates when they would make their trip south he headed to the library. An afternoon of drawing, taking notes and making plans for how he would construct the framework of the bust and he was feeling as confident as ever.

The dawn of the big trip to Częstochowa came quickly around. They set off in a great locomotive, white steam whistling from its cracks and tubes. Water dripped from the radiators causing mammoth icicles to hang from the corners of the carriages. They shook precariously with the motion of the train before smashing into a thousand icy splinters below. The sun glinted off brilliant white lakes as they raced across frozen bridges of snow. Towards dinnertime they pulled into a station where Monika and Jarosław alighted. There was a sledge waiting to take them to their destination. Dirty white tracks in the snow betrayed their route. Ground in muck, oil, soot and sulphur were their composition, which grew thicker and more matted as they drew near to the factory.

A welcoming committee formed of the managing elite, a handful of workers from the timber mill, coils of sawdust in their hair still and the crooked figure of a timekeeper came out to meet them. A frosty looking manager stepped forward to shake them by the hand, barking as he did so, “No time for formalities out here. Unload your materials as quick as you can and make yourselves at home. There’s work to be done. There’s an annual celebration of the leaders ascension into power tomorrow and the place needs knocking into shape! That includes the construction of a towering life size portrait of our beloved master to form its centrepiece.” Jarosław, who had hardly had time to catch his breath, asked what lengths of matchstick they produced. The reply was that the timber mill was capable of sawing any dimensions in width or length that he required. The tone in which the manager spoke made it seem as if he was dubious as to the claim laid upon him that he was the artist that they had so keenly awaited to meet.

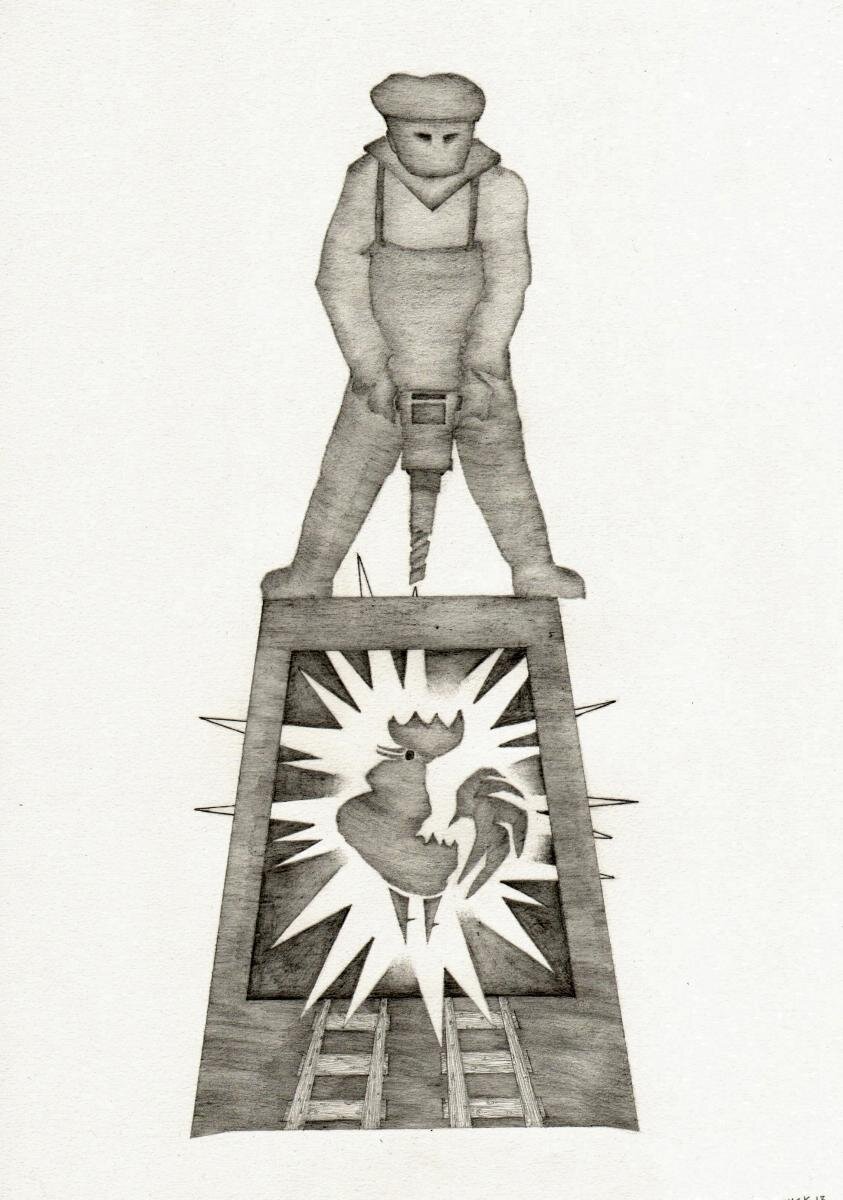

“This Trojan will be at our heels like blazing bellows until the work is done”, said Jarosław to Monika as they retreated down an alley designated to lead to their accommodation.

Jarosław retrieved his pads and tucked them into a bag, then they made for the canteen where they were permitted to help themselves to one piping hot bowl of soup before starting their mammoth task. The foreman of the mill was very helpful, and pandered to their every need. Instructions were sent to different teams in charge of slicing and dicing the timber. Before long the sound of spinning saw wheels and screeching wood filled the air. A pungent aroma of pine fused with that of oil, natural and mechanical. Great cog wheels ground around depositing mounds of blackened dust at their feet. Jarosław swept his brow leaving behind an oily trace. He was trying to keep track of the number of matches that had been produced. It was difficult, the workers marched by every few minutes with another finished product hoisted on their shoulders. They were of varying sizes and headless, bound for the bubbling pot of sulphur in the corner of the factory. Once they had been dipped they were laid out in rows. He sought to snap off a few with difficulty where they had dried together. With ease he dexterously mounted one in his hand and pulling out his pocket knife whittled the stem to a mere splinter. A loose framework constructed of timber offcuts, wire and nails sufficed for the core of the sculpture. To this he artfully attached match by match building up such a close resemblance of the leader in his popular poise. His head was tilted in a characteristic fashion and his eyes gazed dully out. On closer inspection the surface of the face was a sea of red bobbles that formed a perfect undulating swoop from nose to ear.

Upon completion Jarosław stood back and admired his handiwork. Within minutes he was bustled out of the way by a team of officials that descended from an unseen corner of the factory to cordon off the sculpture with red ribbon. Garlands and bouquets of roses were also used to decorate the base of the portrait. For the duration of the time in which he had been slaving away Monika had been in tireless discussions with the management. These were now drawing to a close and it seemed that she might be in sight of her aim. Jarosław’s pretence of proofing was now being brought into play, that and the work he had so assiduously done on the portrait. An opportunity to tour the factory, its design studios and workshops was being posited by the management. It seemed that finally they had some regard for other than only his matchstick building skills. The day after the grand celebration he would be awarded the key to the factory, culminating in a gift from none other than the director himself.

At dawn a monotonous fanfare of trumpets sounded heralding the start of a grey day. Brooding storm clouds having gathered in the night began to softly pelt the factory with snow. By breakfast they had been whipped up into blizzards and were depositing several inches all over. As the gloom lifted, the bust having been left in the centre of the yard for the coming days activities was rendered invisible. A shadowy figure scratching away at its surface with an extendable arm on his broomstick was doing his best to undo the damage. Reports that followed suggested it would be prudent to allow at least a few hours respite in which the sculpture could thaw, before attempting any great consummation in fire. This would also allow crowds to gather in the place of clouds. And so they did, scuffling and jarring for position, vodka shots thrown back here and there with comrades. From the open hatch of a military tank soldiers hollered into the cold air for attention. The masses clamoured and within minutes they were inundated by demands for steaming hot bread-bowls of zurek with warm lashings of lard to be served.

Around three o’clock a gong brought hushed reverent silence down upon the folks in the square. An official stepped forward brandishing a pair of scissors and snipped through the ribbon. He pulled a scroll from his pocket and read out aloud a government directive on the rightful commendation of such subjects as that which he stood before. With a flourish of his hand he produced a battered blue matchbox. Pushing the drawer open and retrieving a match he struck it. Within moments an explosion like that of a sparkler with its customary burst of white light was kindling nicely. A gasp leapt from the crowd as the flames licked towards his fingers, before he flicked it artfully towards the blue touch-paper of the sculpture. An illuminating glare was seen in the frostbitten faces of the audience which showed them for all their gaunt glory. The structure surged in a great conflagration from its base to its tip. Countenances drained of colour were revived as warmth emanated from this white hot raging inferno. As the heat and the light died down a little it became possible to discern blackened totemic remains. Glorified momentarily by the fanning of fantastic flames, only cold charred remnants were visible now. The searing of hellfire that left the skeletal framework of a skull made from spent matches in its wake. Now only cinders remained.

The day after the ceremonial burning, true to their word, Jarosław was conducted on a tour. He was given limited access to areas deemed of interest to him, then guided to the design studios where his practised eye could be put to good use. A leading team member withdrew a portfolio from a plan chest and showed him the latest batch of matchbox cover designs which needed proofing prior to being sent to the printers. Once the task was complete he was borne back down to the yard in the centre. A sledge had been made up with numerous protrusions tied beneath canvas. Puzzling for a minute he caught a knowing glance in Monika’s face before clambering aboard beside her. The signal was given for them to leave and they were whisked away by horses once again. As they sidled out onto the main road back to the station she whispered that the gift had been made for the sole benefit of his artistic career by the committee at the factory. They arrived at the station where they snuck between the great engines. Seeing one bound for Warsaw they loaded their bundle. Climbing aboard they installed themselves in a wood lined carriage, using their spare woollen clothes to keep out the draughts. As they drew out of the town great white arcs rose from the nose of the snow plough before them.

They arrived back to the concrete hum of Warsaw, where they were enveloped by a sea of dust and fumes. Barely able to hear one another beneath the screech of a cement mixer, they retreated to their studio in a bunker tucked away underground. From here the hellish sounds of the city were muffled and they could gather their thoughts in peace. Jarosław tore open the packaging of his present revealing two hundred matches of the desired height.

“You know what this means now?” asked Monika, after having preserved the silence of the moment for a while.

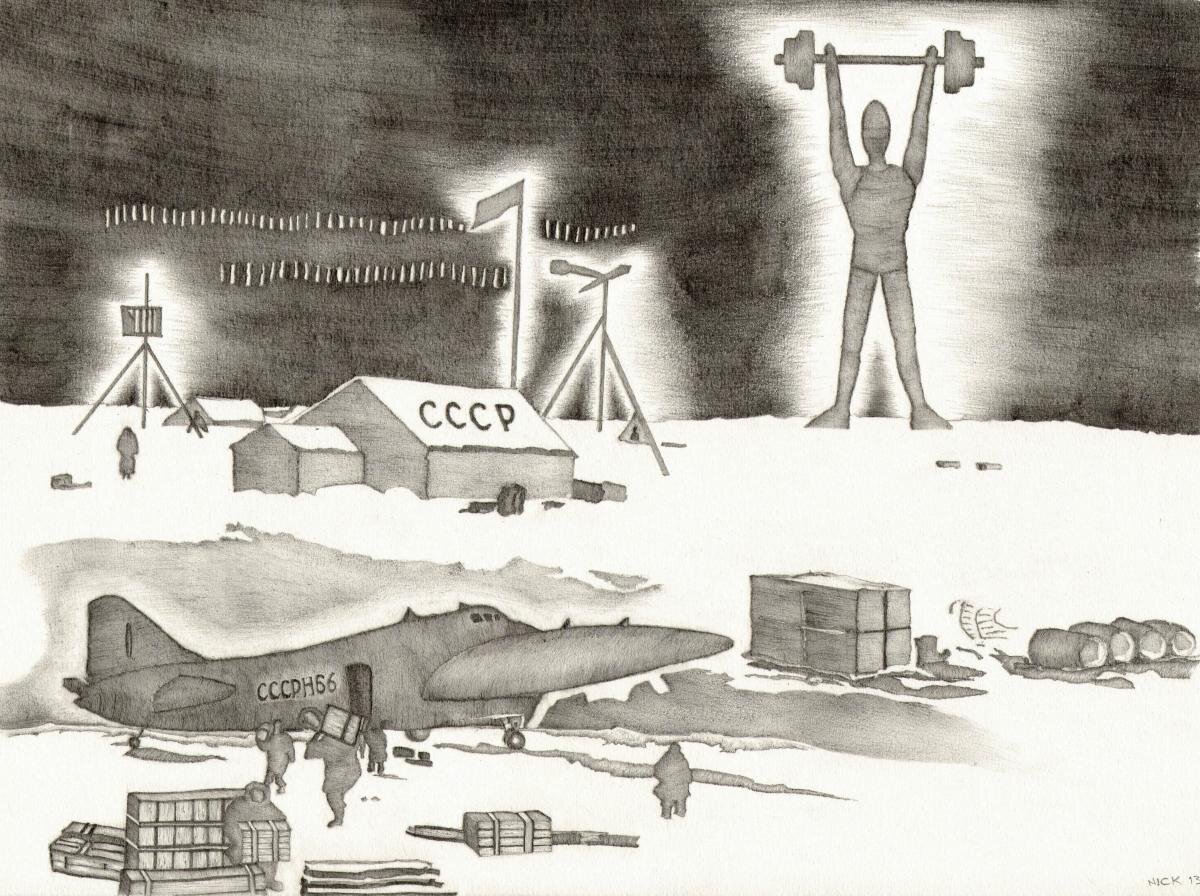

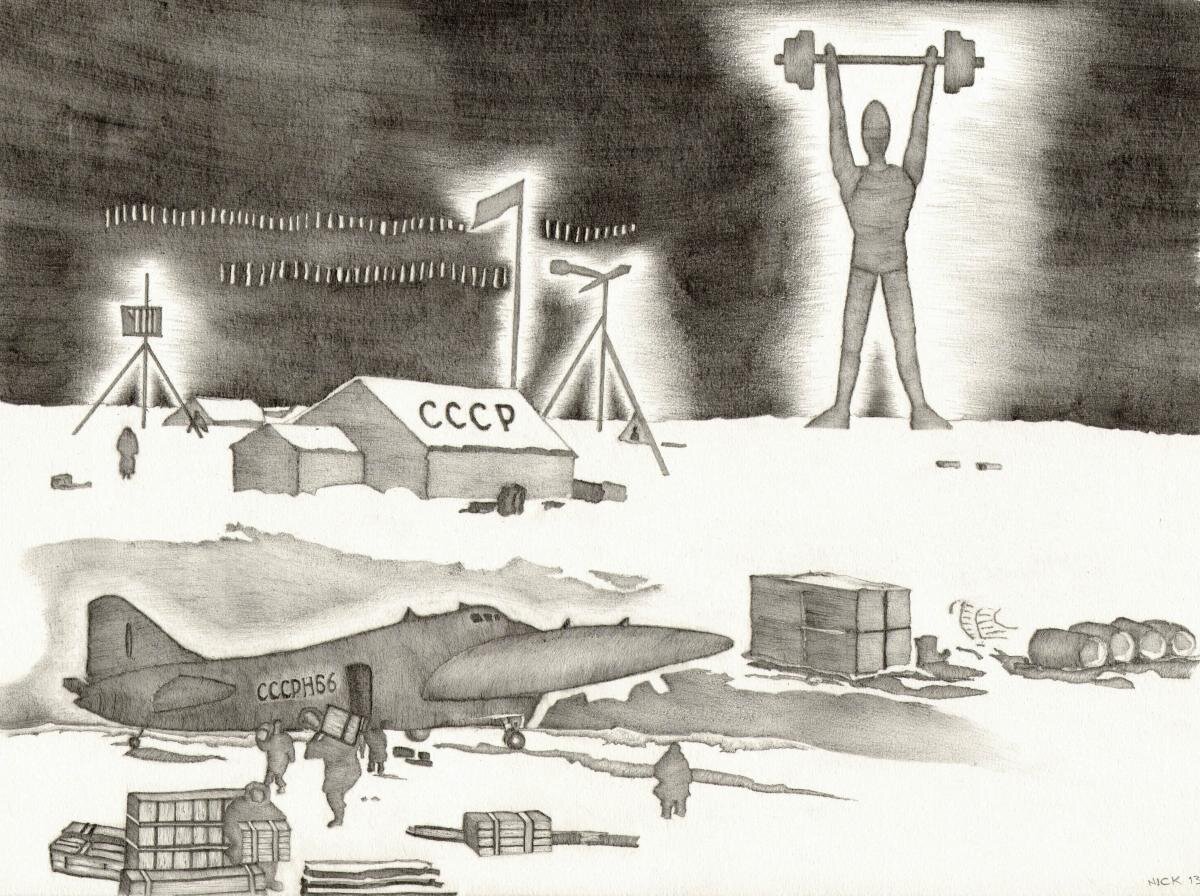

“We have all the necessary products for the performance we wish to launch” he replied. “We simply need to make an aesthetic decision about which drawing we feel would most suit this cloudless starry night over Warsaw. I have been thinking about this and have decided on a drawing that I have been working on recently that illustrates the soviet exploration of the poles. A secret delivery is being made beneath the watchful eye of a shining soviet statue. Polish goods are being brought in by traders and unloaded from a plane in order to preserve their way of life. By projecting this drawing onto the palace of culture with its bleeping beacons and antennas I hope to make the point that this type of activity is always carrying on. If we can time it so that in the moment of explosion when you are recovering from that temporary blindness the first thing that you will see is a stream of huddled figures scurrying beneath with their bags of booty.”

Monika, breathless with excitement, assented with an enthusiastic yes. “I must leave immediately, there is still much to organize. I shall be back in touch with you tomorrow with exact details about how and where we shall launch the artwork from. You must go to your studio and make plans about how you will transfer the drawing to a framework. Then construction must begin ending with the insertion of the matches. Once it has been complete let me know and I shall come at the earliest opportunity to see the finished piece.”

Jarosław’s mind was racing, the task he had before him was great. In order to have the work finished within Monika’s timescale he would have to work through the night. As the dawn poured in a watery light, he could be seen, through a small basement window, in his studio. He looked gaunt and his eyes were puffed up and drooping. An air of triumph was written on his face however. At his feet were several tools, mounds of wood shavings and crumbs of sulphur. In front of him lay a contraption with wings and a pine cage. An inner casing made of balsawood contained all two hundred matches, so that if viewed from a distance the image of his drawing distinctly stood out. In each window tracing paper had been pinned. This was to aid movement whilst it was in the sky. Even the faintest of breezes would be able to aid the craft in its travel. An anchoring tail was decorated with bunting to disguise its function. Any onlookers would be likely to think that the object was a free flying kite.

He called Monika who arranged to pay him a visit as promised. As soon as she arrived he pressed her for details on how the launch of the object was to be executed. She described talks that she had had with a gallery that was keen to be involved in the project and would pay for the majority of the launch. They were offering an underground space that would act as a concealed entry point for its propulsion into orbit. Four rockets would be attached to the corners which would fall away at an altitude of two hundred metres, leaving the object suspended in the air. As it reached this height ignition of the matchstick mural would occur after a preliminary pause for the touch-papers to fizzle down. A momentary explosion of light and then the searing scream of sulphur that would bring black clouds to engulf the spectacle. Against the rooftops it would be emblazoned white hot with luminescent edges. Perfect clarity for a viewing of his drawing that would only last seconds, before being gone with the fading of an acrid smell.

The morning after the launch tongues were wagging. A palpable excitement hung in the air. From each person’s lips a different sequence of events was heard. Those that had seen it were in raptures still. A cosmic bang that exploded in a shower of white filaments. Each streaming down to pinpoints to form a perfectly sharp picture. Some marvelled that it was the birth of some new constellation. It had been seen above the chimney stacks and oil refining plants at about ten o’clock through a haze of petroleum. Through giant shimmering rainbows an eerie light had been lent to the scene. Below the hull of a great plane could be discerned a troop of men bent on their mission of scurrying back and forth. They were carrying bundles marked with the white eagle beneath a light emitting symbol of strength and power. A Russian strongman they claimed it was those that saw it, pumping his iron and exerting a force over lesser mortals. To them it was viewed as a star to draw strength from in order to tighten their oppressive grip over satellite states.

Nothing was heard for several days, then people began to talk again. A careless look or word in the street and the exchange was made. Intelligence deemed to be of no importance exchanged hands to the highest bidder. Every nugget of information was worth its weight in gold.

It was only a matter of time before somebody took the liberty of shopping Jarosław and Monika’s operation to the authorities. That they were in connection with the launch of an offensive image. One that was seen to be corruptive in its make up, and in the fact that it was viewable by many thousands of impressionable young Poles. Jarosław’s every move for the last several years was tracked.

Within days communication had begun with the matchstick factory in Częstochowa. Officials seeking to find out exactly what pretence he had been visiting there under would make sure that no stone was left unturned. Management of the factory were confirming that a couple fitting the description of Jarosław and Monika had visited within the last month. Also that a present had been bestowed on them for the undertaking of an art commission. When pressed for details on this, the nature of the gift had come to light, as well as the project they had been employed upon. Upon hearing of his primary function checking artwork prior to print the authorities took a keen interest in exploring this avenue further. They arranged for a visit to be paid and for an in depth investigation into the connection between himself and the work to be made.

On arrival they were permitted unlimited access to the factories print archive. Searching through filing cabinets and plan chests they puzzled over a multitude of images before them. Only one description of that portrayed in the constellation had been translated to paper and this was all that could act as a clue for them. A further portfolio of artwork was brought to them which they sifted through. The signature at the bottom of the page was brought to their attention, it was that of Jarosław. Poring over in minute detail they scoured his work for signs of the conspirator.

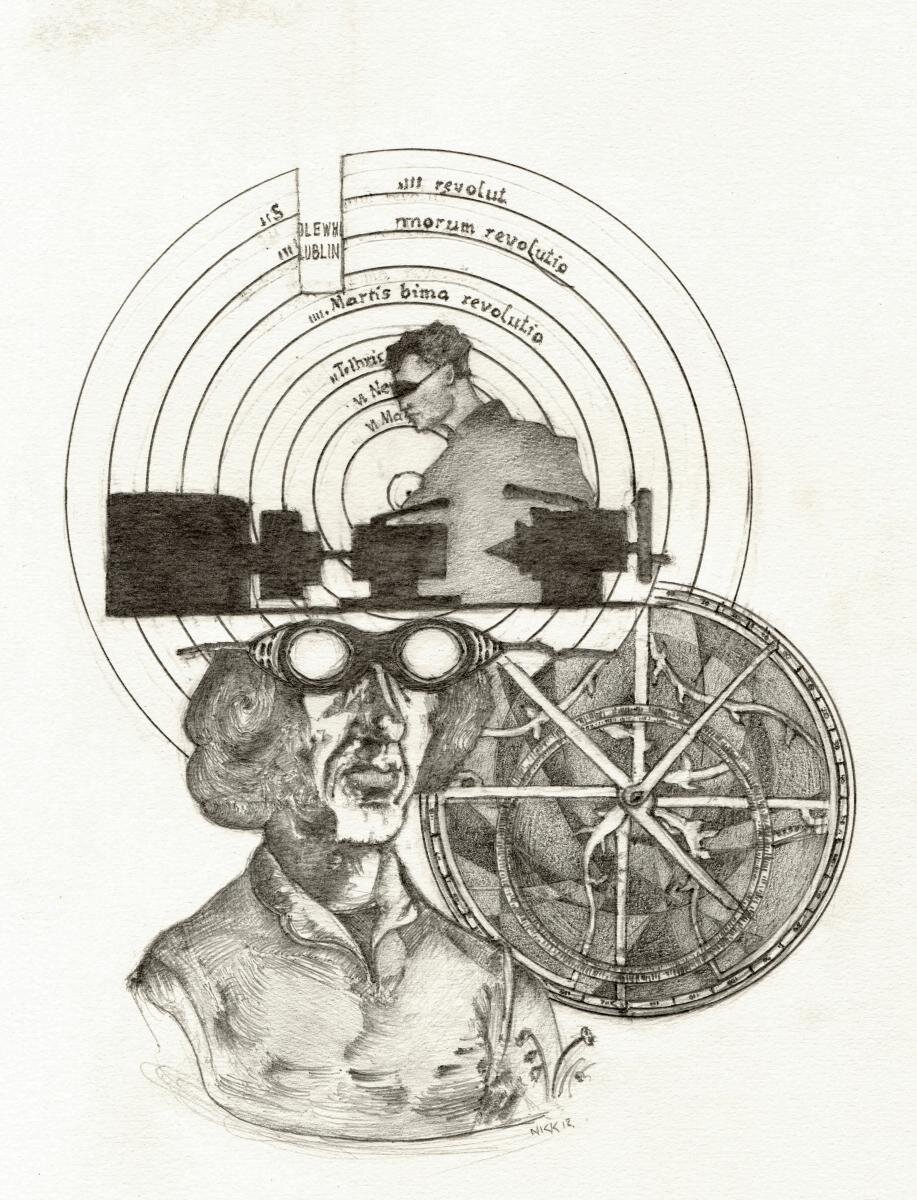

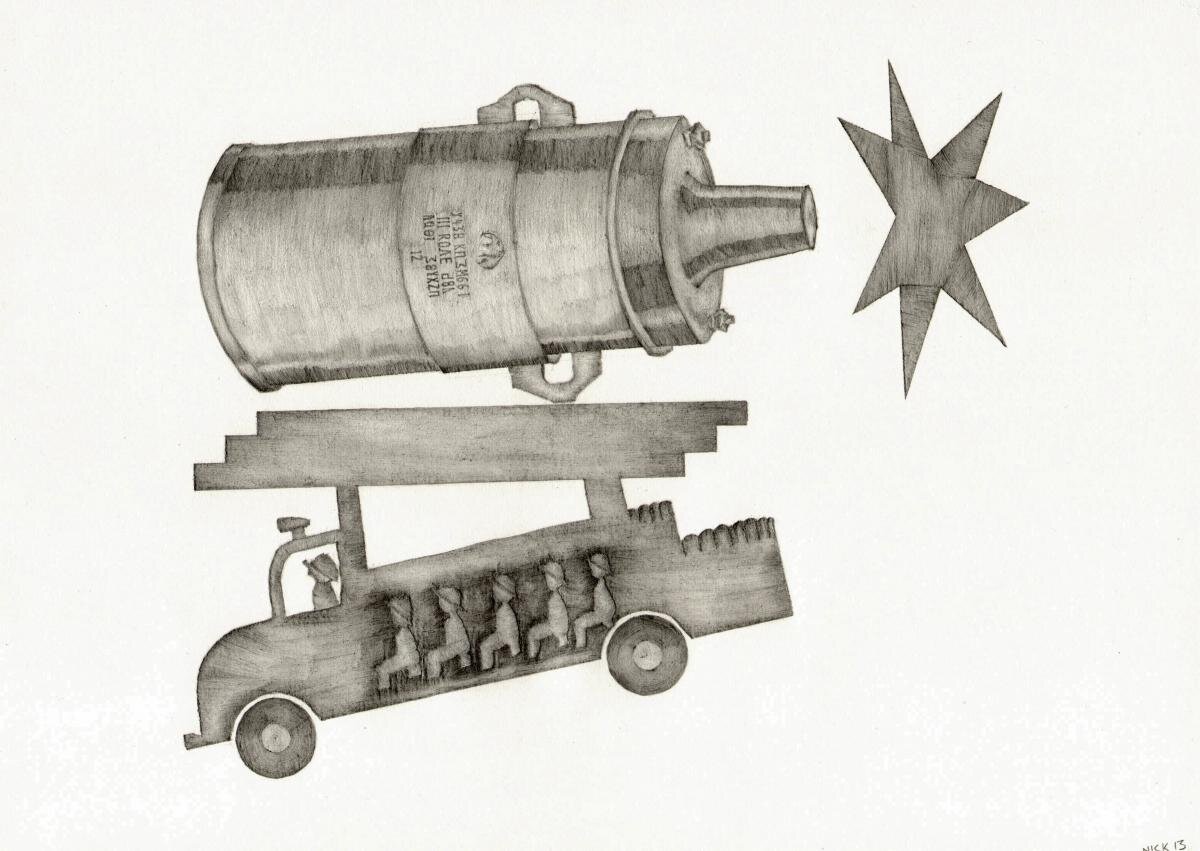

Copernicus blinded to his predictions by the industrial age of soviet manufacture gazed up at them. Heat, noise and fumes to create bionic telescopes that would put his observations to shame. In another an authoritarian figure stood vainly holding his traffic paddle up in order to stop the flow of never ending Polish cars, trains and trucks hurtling past.

The management of the factory, without a passing thought for the work that he had done for them, then came forward with the full story of the matchstick bust portrait. Several workers presented incriminating evidence. One that he had been seen working on the commission with great gusto: “There was a feverish pitch to his activities that culminated in the wheeling out of a contraption bound from hell”. Another maintained as to the pinnacle of the moment, the vision of the leaders face being eaten alive by flames, that a look of satisfaction mingled with enjoyment at the dark display flitted across his features. The short lived blaze kindling a reddish glow upon his countenance like that of a crazed pyromaniac.

Officials ruled that significant proof was to be found here of Jarosław’s true political inclinations. The very fact that he has been allowed to produce these designs and so knowingly influence the public for so many years was a sham.

He hoped to corrupt the common fabric of society through his deceitful drawings but an end shall be put to it. All original artworks and any copies of them must be confiscated and destroyed. The work shall accompany us back to Warsaw where it shall be disposed of at the earliest opportunity. He shall be charged with misuse of his position of authority and his government title will be taken from him. His damaged reputation will ensure that he is never employed by the state again.